The Evolution of an Instructor: My Teaching Narrative

In this section, I'll discuss how my teaching role has unfolded here at JMU. (Note: if you would like to know more about my teaching experiences prior to joining ISAT, I've included a short pre-JMU teaching history section in this portfolio.) The goal of this section is to convey to you my trajectory, depth, passion, and maturity as a teacher. The supporting documents in the teaching section of this portfolio will serve as evidence of my quality. In other words, the artifacts in my portfolio will demonstrate what I've done, while this narrative will relate why and how I've done these things.

At JMU I am primarily involved in teaching courses in:

- Computer programming from basic to advanced level

- Software development and engineering methodology, including agile development

- Social impacts of computing and technology

- Current trends in technology, such as IoT (Internet of Things), VR/AR (virtual/augmented reality), blockchain and cryptocurrencies (e.g. bitcoin)

In addition to these areas, I have also taught critical thinking, Japanese language and culture, and have participated in a wide variety of other teaching experiences.

Overview of Teaching at JMU

Since coming to JMU, I have continued to broaden and deepen my knowledge and skills in the two areas that Lee Shulman, an expert in teacher professional development, describes as the pillars of effective teaching:

- Subject Matter Knowledge: knowledge about the subject that one is teaching, and

- Pedagogical Content Knowledge: knowledge about how people learn and the techniques teachers can use to support that learning.

I have worked constantly and consistently throughout my time here to become a recognized expert in my field and also a recognized expert in the ways in which I can foster understanding about my field among the students that I interact with.

Maintaining Subject Matter Knowldege

I am primarily responsible for teaching courses in programming and web development. These domains are still young and VERY volatile. The languages, techniques, technologies, and hardware used by software and web developers change rapidly and may become partly or largely obsolete on time scales that range from eighteen months to two years. To make this more palpable, here is a list of things that I now teach regularly that did not even exist (or were not popular/mainstream) in 2006, when I started in ISAT:

- Pre-Tenure

- Touchscreen phones, i.e. "smartphones" (LG released the first one in 2007)

- Mobile apps (iOS appeared in 2007; Android appeared in 2008; app stores came later!)

- Stack Overflow (launched September 2008)

- GitHub, home of >90% of open-source software (launched 2008)

- HTML5 (introduced 2008; adopted 2014) and CSS3

- NodeJs, i.e. server-side JavaScript (2009)

- Post-Tenure (still working!)

- iPads (and tablet computers in general; iPad released April 2010)

- Cordova--basis for modern hybrid apps (released 2011)

- Agile software development (IBM used Scrum for 80% of project teams by 2012)

- NoSQL Databases (MongoDB released 2009; "MEAN Stack") coined 2013)

- VR/AR Headsets (Oculus Rift launched 2012)

- Single-Page App Frameworks, i.e. SPAs (React, Angular, Vue take of starting 2015; now dominate app dev)

- Progressive Web Apps aka PWAs (term coined in 2015; still in flux)

- IoT aka the Internet-of-Things takes off in 2017 (31% increase in devices)

- Blockchain and Cryptocurrencies (Bitcoin released in 2009, but took off in 2017)

- Test-Driven Development (TDD is still gaining momentum)

- ...and A LOT more...

I spend an ENORMOUS amount of time just trying to keep up with the latest developments in the field. (Here is a partial list of things I've spent significant time learning.) There are many, many things that I simply don't have time to learn about. I spend a significant amount of time just figuring out which technologies are the highest priority for me to learn next!

In order to deepen my subject matter knowledge I have leveraged the interests, enthusiasm, and free time of students to help me stay current. I sponsored weekly "hacking sessions" from 2008 to 2013 so that I could involve students in my exploration and also be responsive to and knowledgeable about the technologies they would like to use for solving problems. I have mentored a large number of senior projects, many of which required me to work hard to keep up with my students, who chose cutting edge platforms upon which to build. I have attended conferences and workshops focused on software development such as the SXSW Festival in Austin, TX (2016, 2017), the 2017 Samsung Developers Conference (where I placed in a hack-a-thon) in San Francisco, and the Agile Software Development 2011 Conference in Salt Lake City where I met, interacted with, and learned from some of the most famous members of the agile software development community like Alistair Cockburn. I have regularly taught a number of special topics courses, frequently without compensation or having it count toward my teaching load. I have also kept my skills sharp by employing them in the service of outside consulting clients and on research grants. I feel comfortable saying that I know as much or more than any other person at JMU about web and mobile app development.

Deepening Pedagogical Content Knowldege

Likewise I have worked to deepen my pedagogical content knowledge. I have attended a broad array of professional development conferences, workshops and symposia. I observed over 50 classes and discussed effective teaching strategy with over 1000 students in my service as a Teaching Analysis Poll (TAP) Consultant. I conducted over 700 interviews with students and analyzed their written semester narratives. I have also benefitted (and benefitted my students) by being the recipient of TAP analyses in many of my classes. I spent a year exploring the characteristics of the “millennial generation” as a Madison Teaching Fellow. I have engaged in extensive reading and research to deepen my pedagogical understanding such as my choose-your-own-grade research, and the ongoing development of a web-based learning management system (LMS) I am developing called Code4YourLife. I have reviewed articles for journals and conferences related to information systems and computing education such as the Journal of Information Systems Education and Computers & Education. I have taught in a number of different types of classes, contexts and formats including lecture courses, lab courses, discussion sections, independent studies, international programs (SERM), and through the development of a summer study abroad program to Japan. I have spent a great deal of time discussing effective pedagogy as a member of team-teaching teams and through one-on-one conversations colleagues have sought to have with me. I have been a part of building cross-campus, interdisciplinary partnerships designed to blend teaching, research, practice, and experiential learning.

All of these efforts have resulted in a number of concrete achievements. I am known across campus as an expert in pedagogy and course evaluation and am sought after to participate in and lead groups of faculty like the Faculty Senate Academic Policies Committee and task forces on academic rigor and course evaluation, both at the departmental and university level. My syllabi have evolved to become what Ken Bain refers to as "promising syllabi." I have produced numerous course websites and course videos as well as high quality labs. My subject matter and pedagogical content knowledge expertise continues to be recognized as I initiate and am asked to participate in grant-funded research, build websites for external and internal clients, and deliver invited talks to colleagues. I developed the pre-semester questionnaire technique. I've been able to publish papers on teaching and learning and present them at refereed conferences. I led the effort to produce BSISAT Program Goal K, and also contributed language for the JMU faculty handbook that sets standards for the quality and frequency of instructor feedback. Of the senior projects I've mentored, one earned the ISAT Integration Award, two earned the Best Honors Thesis Award, and another was published as a poster at the American Wind Energy Association's annual meeting in Dallas, 2010, while yet another publication has become one of the most downloaded papers in the entire STEM to STEAM field!

My Evolution: Semester-by-Semester

The next sections will describe the evolution of my teaching philosophy and practice.

2006 Fall - 2008 Fall: Getting Acclimated

During the first two-and-a-half years I was in ISAT, I pretty much followed the lead of the IKM Academic Team. I coordinated my course schedules with the other faculty who were teaching sections of the same course. I gave the common exams and assignments. I calculated the grades using the same formulas. For courses that I taught alone, i.e. ISAT 348, I had the students focus on building proficiency in web development and worked with them to develop holistic grades that were based on project work. I did not have tests or homework, but rather had them work on tasks that more resembled the kind of work they would do as web development consultants.

Meanwhile, I was working on my dissertation, which focused on teacher professional development, assessment theory, multiple-choice question development, and web programming. My deepening understanding of psychometrics led me to be increasingly skeptical about the practices with which we assessed students day-to-day. My skepticism is captured most succintly in my explication of the choose-your-own-grade philosophy. It wasn't until I read Alfie Kohn's Punished By Rewards that I felt truly compelled to go in a new and different direction.

2009 Spring: The First Choose-Your-Own-Grade (CYOG) Course

In January of 2009 I told all of the students in my three sections of ISAT 252 that they would be allowed to choose their own semester grades with no strings attached. The only requirement for the course was that students meet with me face-to-face at the end of the semester, present a portfolio of their work, and inform me of the grade they would like for me to report to the registrar. I made it clear that they did not have to attend class, take any tests, read any chapters, or do any assignments of any kind.

However, I spent a great deal of time and energy working to convince them that it would be a very worthwhile use of their time to devote their energy to the class. I appealed to their economic sensibilities--college is expensive and it would be a waste of money not to make the most of the opportunity you have in this class. I spent a lot of time in individual discussions with students so that I could learn their interests and help them to design assignments for themselves that were in line with those interests. I made it clear that I would be available for them if they would only engage with the material.

I set up a video camera in my office and every day after class I would talk about the experience, and, as such, kept a video journal of my experience. I also video taped all of the exit interviews with the students and kept their end-of-semester portfolios for analysis. Here are some of the things that I found:

- Attendance improved

I was amazed to see that people actually showed up more with this new arrangement - Engagement increased

Students reported spending more time outside of class and worked harder on their programming assignments. Class time was much more lively as students were much more proactive about asking how to solve problems with their programs. I had as many as fifty students come to hacking sessions on Monday nights. - Everyone took all of the tests

Even though they weren't required, everyone showed up to take the exams, even though they were given in the evening outside of class time. - The quality of work increased

Sixteen out of the seventeen teams that semester turned in end-of-semester programming projects which were head-and-shoulders above previous semesters in terms of challenge, complexity, and quality. Perhaps my favorite was called Robot Game, and was a video game complete with soundtrack, gravity, collisions that was built entirely by a student team that had never programmed before. Users could even create their own custom levels for the game with their own music by using a special Excel spreadsheet format that the students had created. - I learned more than I ever have

Because students were not restricted to the topics on the syllabus that were normally chosen by me, they pushed me in many new directions and I had to learn a bunch of new features of the VB.Net programming language in order to support them. - I understood just how much power I held

Until you abdicate your power over the grades, you never really understand just how powerful you are as a professor. In fact, to the extent that students care about their grades, the professor is nearly all-powerful in the classroom. I realized ways that I had abused that power in the past and the friction it had caused. - Students opened up to me in ways they never had

Because they were no longer worried about their grades or looking “stupid” in front of me, I got many more questions than I'd ever gotten before. Students talked a lot more about their lives outside of class and how those lives impacted the time that they could or could not spend on ISAT 252. - We all had a lot more fun

They weren't stressed about being judged, and I wasn't stressed about having to judge them. We were free to fully engage ourselves in writing software and having fun doing it.

There were some not-so-positive results as well. Some students, particularly the students with high GPA's, were at times more anxious about their performance. They were reluctant to judge the quality of their work on their own. Many complained that since programming was not something they enjoyed, that not having grades hurt their motivation to complete work for the course. I also had a hard time competing for students' time against other classes where their assignments were graded. Students were pretty uniformly lenient on themselves when it came time to assigning grades, but not as lenient as I had thought they might be. Seventy percent of them gave themselves a flat-out ‘A' for the course, whereas the other 30% gave themselves an A-, B+, or a B. I may have had only one or two B- grades that students assigned themselves. Interestingly, but in retrospect not surprisingly, the students with higher GPAs tended to be more critical of their work and to give themselves lower grades. The tendency for competent people to underrate their abilities is referred to in psychology as the Dunning-Kruger effect and has been observed in a wide range of areas of expertise.

Considering the quality of the work the students did that semester, and the excitement I was experiencing as a result of my perceived success, I was not prepared for how strong a negative reaction I received from some of my colleagues. We had two long meetings the following semester in which I attempted to explain the research and theory behind my approach. Some questioned whether or not what I was doing was in violation of the faculty handbook (it’s not as far as I can tell). However, of the seven or eight people who attended these meetings, three or so were intrigued and supportive of my efforts, three or so were either mildly or strongly against my efforts, and one or two were on the fence. I took the mixed reaction as a strong indication that I’d hit on an excellent topic for research.

2009 Fall - 2011 Spring: Portfolios, Pre-Semester Questionnaires, and Weekly Self-Evaluations

During the next two years, I developed three new course elements that would remain a part of my teaching strategy through the 2016 Spring semester: 1) portfolios, 2) the pre-semester questionnaire, and 3) weekly self-evaluations. The pragmatic, holistic nature of portfolio-based evaluation is a good match for the ISAT Habits of Mind. (In fact, the Assessment Committee has been trying to develop a program-wide portfolio for a number of years now.) The questionnaires and self-evaluations are described in other sections of this portfolio.

After being severely chastised by several colleagues in the fall of 2009 for implementing choose-your-own-grade (CYOG), I became fearful about openly doing that research as an un-tenured faculty member. To be sure, while I was afraid to put "choose-your-own-grade" explicitly in writing, nearly 4 out of 9 pages in my Fall 2009 Syllabi were spent explaining to students why grades did not support their learning effectively. The other parts of the syllabus focused on how to produce an effective portfolio of work. In short, I spent my time teaching students how to recognize the difference between good work and not-so-good work, and help them to develop a collection of artifacts that they could show to a classmate or potential employer to convince them of their new skills.

2011 Fall: Applying for Tenure

In the fall of 2011 I submitted my application for tenure. This emboldened me to pick up my experiments with CYOG where they had left off. By this time, the pre-semester questionnaire and the weekly self-evaluation were standard fixtures in my courses. I had a mechanism to jump-start my relationship with each student, and a way for the students to be proactive about monitoring their own progress throughout the course. I built an automated system that would send out the weekly self-evaluation along with several reminders to those who didn't complete it right away.

I wanted my courses in Fall 2011 to match as closely as possible the level of performance that I observed in the Spring 2009 semester when I first did CYOG. Unfortunately, the students' performance wasn't as strong as I had hoped. To be clear, their performance was perfectly adequate and within normal limits compared to a "traditional" approach to teaching. They continued to work in teams and build software projects that they presented to me and to their classmates. However, they didn't show the same level of enthusiasm, and there wasn't the same degree of creativity and passion that I had seen before.

2012 Spring: Introducing Expectancy-Value-Cost Theory

In order to gain a handle on why students weren't responding as enthusiastically as they had in 2009 Spring, I consulted with Kenn Barron and Chris Hulleman, two psychologists at JMU who specialize in motivation theory. They were in the process of working on an instrument to measure motivation based on what they called Expectancy-Value-Cost theory. Conceptually, the formula for motivation looks as follows:

M = E * V - C

In English, motivation is equal to the product of expectancy times value minus cost. "Expectancy" is a person's subjective belief that they could be good at something, i.e. their confidence that they have or can develop skill. "Value" is the degree to which a person believes a skill or topic is worth knowing. For example, computer programming might be seen to be more valuable knowledge than, say, speaking Latin. "Cost" is the time, energy, and/or money a person will have to spend to acquire the skill. Since the E * V relationship is multiplicative, as either expectancy or value approaches zero, a person's motivation also approaches zero. The higher the cost, the less likely a person will be motivated to acquire the skill, but cost is not as important as either of the other two variables.

As an instructor, the goal is to convince students of two things:

- You absolutely have the capacity to learn this! (i.e. boost expectancy)

- This thing is absolutely worth knowing! (i.e. boost value)

Having boosted the E and V, the goal should be to reduce the perception of cost. This can happen by using one's experience to show students a path to learning that will be more efficient.

In 2012 Spring, I delivered Dr. Barron and Dr. Hulleman's instrument to my class along with the pre-semester questionnaire. This questionnaire was only delivered once during the semester. While it gave us a single point in time reference of students E, V, and C values, these values were measured before the beginning of the semester and before any interaction with me, the instructor. Also, having only a single data point was not very useful in diagnosing why students weren't as motivated as I'd like since there was no reference for comparison.

Ultimately, I just contributed my data to Kenn and Chris' study. They eventually published a paper with validation of their instrument. Even though the quantitative results weren't super useful for me, I began to develop a better sense for how to better motivate students to learn. I was able to use Kenn and Chris' motivational framework as a lens through which to interpret the end-of-semester narratives and interviews that I was conducting with the students. I was able to listen for expressions of lack of confidence, lack of value, or perception of cost, and counter them as appropriate. I also used this understanding to make classes more engaging.

2012 Fall: Introducing Positivity and Mindfulness

In 2011 Summer, I attended Agile2011, a major industry conference for the agile software development community in Salt Lake City. One of the keynote speakers was a researcher from UNC Chapel Hill named Barbara Fredrickson. Dr. Fredrickson's field is positive psychology, and she was developing a theory that showed that cultivating a positive attitude has numerous benefits to one's cognitive, emotional, and physiological health. In her book, she describes it as the "broaden and build" theory, and it is the polar opposite of "fight or flight." In the book there is a relatively easy-to-use instrument that allows you to measure your "positivity ratio" at any given point in time. I implemented this instrument in Qualtrics and began delivering it to my students along with their weekly self-evaluations so that they could monitor their level of positivity from week-to-week.

In addition to positivity, Fredrickson also recommends cultivating mindfulness. I read The Power of Mindful Learning by Ellen J. Langer, a Harvard psychologist, who also conducts positive psychology research to demonstrate the primarily cognitive benefits of cultivating mindfulness. As a result of reading Langer and Fredrickson's works, I began to spend five minutes of each class period teaching my students to meditate. There is a great deal of evidence to support the connection between even very short meditations and significant improvements in knowledge retention and test performance. I also added a measure of mindfulness to the surveys delivered to students: one at the beginning and one at the end of the semester, to determine if a semester of meditating could improve students' level of mindfulness.

The students responded extremely positively to these interventions. Many of them reported in their end-of-semester narratives and interviews that they had begun to meditate on their own outside of class, and that they were teaching their friends and families how to meditate as well. Students reported how they were becoming more aware of when negative thoughts and feelings were creeping into their consciousness throughout the day. The overall tenor of the class became much more relaxed and enjoyable for everyone present. Of particular note, the 21 students in my GISAT 160 section had an average response of 4.81 out of 5.0 on question #12 of the ISAT course evaluation: The course helped me to gain an appreciation for the subject. I think this is significant, particularly since this is a GenEd class that usually gets pretty low ratings, and these results encouraged me to find other ways to boost student well-being and motivation.

2013 Spring - 2014 Spring: Mastery vs. Performance Orientation

For the next three semesters, I continued to fine tune the types and schedules of data that students were providing in the pre-semester questionnaires and their weekly self-evaluations. From student feedback and from observing them in class, I became aware of a new dimension of their personalities. Following Benjamin Bloom's (1984) findings that a mastery approach is superior to a traditional performance approach in terms of student learning, I discovered that at the individual level students can have either a mastery-orientation or a performance-orientation.

Students with a mastery-orientation are interested in learning for the sake of learning--i.e. they are intrinsically motivated. Conversely, students with a performance-orientation are motivated by wanting to get high grades, or not perform relatively worse than other people in the class. Their learning tends to be more shallow and shorter-lived. There are things an instructor can do to encourage students to adopt a mastery-orientation, and also ways to de-emphasize facets of the class that lend to a performance-orientation.

To be sure, peforming well on a task is absolutely a good thing, but not when the resulting score becomes more important than the underlying knowledge or concept. To focus students' attention on mastery concepts, I added a new instrument called the Achievement Goals Inventory (AGI) and then reduced the frequency of the combined positivity, AGI, mindfulness, and EVC instruments to being delivered only once every 3 weeks, or 5 times per semester. Not only was this calculated to prevent students from getting burned out on surveys, but it would also hopefully provide me with a nice data set for analysis at the end of the term.

Unfortunately, however, the effectiveness of the CYOG strategy seemed to be weakening a little bit each semester. It was clear that the students would like to have fewer surveys to fill out. At the same time, I couldn't help but wonder if the students' reduced enthusiasm was merely a reflection of the fact that this new mode of interaction had become more routine for me. I wasn't as nervous and energized as I had been in 2009. Also, it was clear by this point that word was getting around JMU about my CYOG approach. I began to see students showing up in my classes who were not ISAT majors, and who had clearly enrolled in my class to get the "easy A."

Concurrently, one of the most consistent complaints students had about my courses was the lack of "structure." Since the courses actually had quite a bit of structure (please refer to the syllabi), I determined through conversations with them that what students meant by "structure" was actually "due dates." Students wanted me to give them absolute times when specific assignments would be due. Since I allowed each student to work on different things from all the other students, this was not a request that I could easily accommodate. In 2014 Fall I came up with a potential solution.

2014 Fall - 2015 Spring: Introducing the Points-Accumulation System

In response to students' consistent requests that I provide them with specific due dates and pressure to perform, in 2014 Fall I gave them the option of choosing either CYOG or a points-accumulation system. With the point system, the grade for the semester would no longer be self-selected. Instead, students would have to complete a certain number of "badges," each of which was tied to a specific set of knowledge or skills. Students could still select which badges to tackle, but they couldn't pass the class without scoring a certain number of points.

Even though the students had specifically asked for this system, as it turned out, none of the students actually chose to follow the points-accumulation strategy for the semester, even though some of them openly admitted that they knew they would not be as productive as they would like if they didn't choose the points system. One student summed up the situation as follows:

Morgan, I understand what you're trying to do in this class, but when it comes down to it, if I have to choose whether to spend my time on this class or another class, I always remember that I'm getting graded in the other class. Your class always gets put on the back burner.

2015 Fall - 2016 Spring: A Major Turning Point

In the 2015 Spring semester I had an email exchange with a student that completely demoralized me. In a nutshell, despite insisting that I was the "most intriguing/inspiring professor" he had ever had at JMU, he had decided not to come to class at all that semester since he knew he could pick his own grade and he needed to focus on other classes more. He was frank about his decision, even when confronted with how illogical and unethical it was. It was after this exchange that I decided that while CYOG might work in an atmosphere where a significant number of other professors were doing it, it did not serve students best in a context where I was the only one doing it. And in several years of trying, I was never successful in convincing even one other professor to try it.

In the 2015 Fall semester, I let my students know that CYOG was no longer an automatic option --they had to earn it. Instead, the default option was that they had to earn points by completing badges. They still had an enormous amount of choice in how to spend their time in the form of a broad menu of badges. Points were based roughly on how many hours students spent on the class, following from the research indicating that time-on-task is the only reliable predictor of learning. The thought process that led to the hours-to-points calculation was explained in detail in the syllabus.

The students hated it. I didn't really like it either. In the 2016 Spring, I tried it one more time, but it was still awful. It took me two semesters to figure out that I had hit on exactly the worst conditions for allowing students to synthesize happiness. It turns out, nobody wants to know how the sausage gets made, and that goes doubly for how grades are calculated. I was explaining my grading philosophy in super-fine detail because I felt students would really want to know how they were being evaluated. They would rather not have it explained. I didn't figure this out until the middle of the 2016 Fall semester.

2016 Fall: Regrouping

Given the failures of the past two semesters, I found myself back at the drawing board.

In 2016 Fall, I went back to CYOG with a newly explicated philosophy because I disliked it less than I hated the points-accumulation system.

2017 Spring - Present: Explain Less. Expect More.

My new motto is: "Explain less. Expect more." I have consolidated all of my courses into a single website. I've found that students don't hate the points-accumulation system if you don't tell them what the points represent. On the other hand, they are still pretty bad at prioritizing and managing their time.

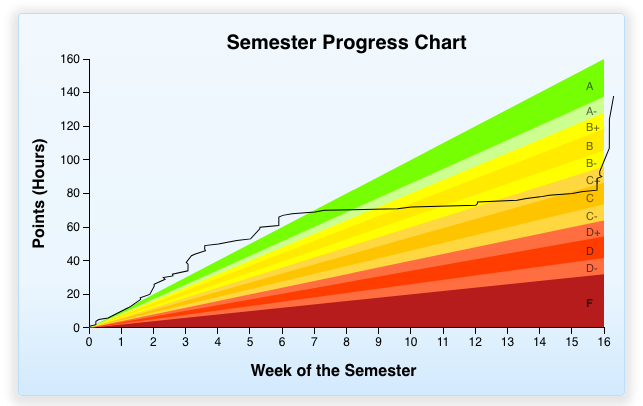

This chart represents the average student in one of my 252 sections this past spring. All of them did extremely well over the first 5-6 weeks when there was still a lot of handholding. However, mid-semester when I set them loose to pursue the course material following different paths of their own choosing, their effort basically flatlined. It did not pick up again until the end of the semester when they all realized they needed to turn in work to get enough points to pass.

Although I am no longer using it at all, I still believe that CYOG could work with undergrads under the right conditions. I still believe that if all of our courses operated according to its principles, that we would see greatly improved outcomes. Until I'm able to convince everyone else, or move to a place that believes like I do, I'm going to have to search for a happy medium.

Summary

Taken as a whole, I believe this evidence demonstrates that I am an excellent teacher. In every semester, I have been committed to my craft and energized by the challenge and the opportunity to help students mature and develop as people and as professionals, becoming enlightened citizens who lead meaningful and productive lives. Furthermore, not only have I improved as an individual, but I have become known as an expert on pedagogy within JMU and internationally, and am frequently consulted by colleagues and asked to present at meetings, workshops, and symposia. My efforts therefore have resulted in an overall increase in the quality of teaching at JMU, particularly within ISAT.